One Hundred and Twenty-Five

I took the train back home and fell asleep the moment it started moving. The ticket inspector woke me up minutes later, and I showed her my ticket, then fell back asleep. The sun was setting when I woke up, and in the distance, the sky glistened with gold and victory. When I got out of the train station, the city seemed utterly unchanged. I watched as the same buses came and went; the man who sold newspapers still there, in his booth, surrounded by flashy magazine covers. A teenager asked for a cigarette and was intent on paying for it. I told him I didn’t want his money, but he insisted. I took a taxi to our apartment and asked the driver to let me off at another address. I felt like walking the rest of the way because I wanted to see the supermarket just around the corner, and the antique shop with the expensive Persian carpets on display. The fluorescent sign outside the gym, the coffee shop just across the street, they were all there, like breadcrumbs, to remind me of my way back.

The key still worked. I took the elevator because my suitcase was too heavy and I was too tired to drag it up the two flights of stairs. I could, for once, use the elevator. When I got to the door, I was afraid to unlock it. I waited in the silence of the corridor, hoping to hear something moving in the apartment, but nothing stirred inside. I unlocked the door and the moment I opened it a repulsive smell assaulted me. I got in and closed the door behind me, afraid that it might travel around and disturb the others.

Nothing had changed. My note was still stuck to the fridge. Inside the freezer, tomatoes had rotten to ash. The curtains were heavy with grime and dust, the sink in the bathroom calcified. I left my suitcase in the hallway and started opening the windows. I did not yet dare to go into our bedroom, afraid that it might rekindle painful memories. I knew I could stall the wave of memories, because, after all, I was aware of what they were. I would see your clothes on the bed and imagine you taking them off before bedtime, the yellowish light on the bedside table throwing warm shadows all over your body, the hairs on your chest golden, like gossamer in the morning. I was already imagining everything, with the clarity of one who had understood the situation a long time before and was only playing along so as not to disrupt the natural course of things. I felt like I shouldn’t dwell on those memories, that I shouldn’t go into the bedroom. Not going in was part of that natural course of things. I might have seen it in some movie, the protagonist avoiding certain places, knowing full well that he would be unable to stop some of those memories from resurfacing. To us, in the audience, that always seems exaggerated, a shallow thing to do. But then I was doing it as well, avoiding the bedroom.

I took the garbage out and washed the two cups in the sink. I bleached the bathtub and the drain, wiped the bathroom mirror clean. The water was first rusty red, but then it cleared. The smell inside the house began to change. But I still didn’t go into the bedroom. I went out to the supermarket around the corner to buy some groceries. The cashier recognized me and asked where I had been all that time. I told her I had found work outside the city. Was I back for good? I put the coffee in the bag, then the fresh bread, then the cheese. I didn’t know what to tell her. Maybe, I said, I’m still figuring out what to do with my life. I gave a nervous laugh to show her that I wasn’t too serious about it. She smiled and placed her right palm on her chest. I hope you figure it out soon. I thanked her, grabbed my bag of groceries and went out.

The nights were beginning to get cold, the dying light at the edges of the horizon like a cry for help. The approaching night relentless in its advance. Neon signs competed with the dying sun. Some of the shops lining the street were closing, the owners looking at me, furtively, and with an air of despair, as if I were some sort of alien figure who was a harbinger of a darker age. Cars were idling on the streets around me, people returning from work. I envied them because they had decided to stay in the city while I was running away, from what I don’t know. But the atmosphere calmed me; it made me think of the afternoons after work I spent with you when I was tired but thrilled to see you. The happiness that gave me the energy to spend time with you and laugh with you while music inhabited the background.

I got back to the apartment and turned on the fridge. It whirred to life. I turned on all of the lights, but I still didn’t go into the bedroom. I decided to cook some pasta since it was the only thing I could make on the spot without using too many pans. I washed one of the pots and turned on the burner. The warmth coming from the boiling water made the windows sweat. Finally, it felt like home. I turned the TV on and let it run in the background. I put the pasta in the water and lowered the flame. I wanted it to cook slowly as if seeing it boil brought comfort. I took a bottle of wine out and opened it. The taste and smell of wine made me hungry. I cut some of the cheese into little pieces and placed them on a plate. A man on TV was speaking about immigration. The climate forced people to abandon their homes to move to other countries. They moved in groves, like groups of nomads in search for new ground.

I poured some more wine into the glass.

And there you were, frying the vegetables in a pan, making them jump, the way chefs do on TV. You were wearing a white t-shirt that said ‘double cheese makes life better’ and a pair of black trousers that made your long legs look even thinner. We were laughing, and I was recording you with my phone. It was the evening in which we had gone to a vintage clothes shop to look at some stuff and returned home famished. When we went to the supermarket to shop for groceries, I felt like I was going to faint from the hunger.

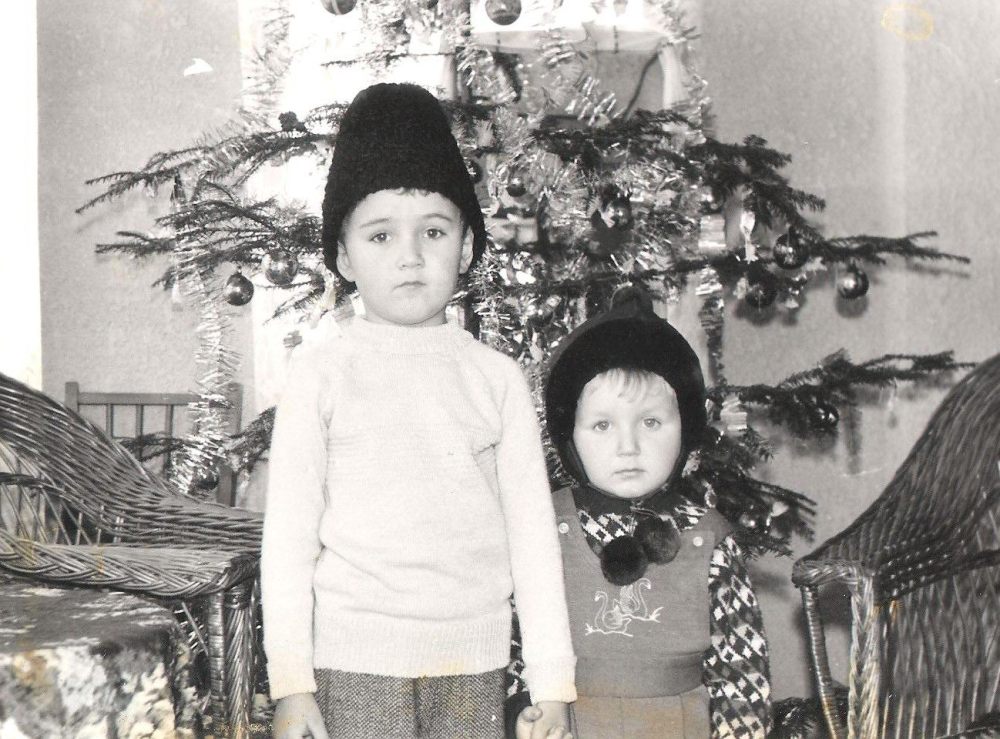

Once we got back home, it was already well after nine pm. You held onto the pan with your right hand and placed your left hand on your groin. If there had been a reference into your gesture, I didn’t catch it, yet I laughed anyway because your hair stood in a certain way that made you resemble a very young version of you. Perhaps the little boy who had been told that he was suffering from some sort of syndrome and had to be medicated to keep his body from growing out of proportions. You had told me about him, the little boy, a while back when we said each other stuff one night, and you listened in silence while I told you the story of my life. When you spoke about the doctor and the things he said to you I wanted to hold you tight as if to let you know that the doctor had been very wrong, that you turned out to be the sexiest man I had ever laid my eyes on.

Stay like this, I wanted to tell you, there’s no need to change anything.

Up went the vegetables, and then back into the pan. You were actually good at it. Your glasses were foggy from the steam. Is it a video? I nodded because I didn’t want my voice to be heard on the recording. I can only hear my laughter now. I can see the two glasses of wine on the kitchen table, and I can listen to the music in the background. I remember not wanting it to stop, that moment. I wished the world left us alone, there, in your kitchen. Let us live, and we’ll let you spin, as you’ve done for millions of years.

You were cooking rice or some variation of it. You always asked me what I wanted to eat, but I never knew what to say. You were disappointed by that, but to me everything with you was new, even the rice you were cooking. We fed each other chips and dried veggies while dancing. We decided to eat outside, on the little table you had put on the balcony, where I went for a smoke every once in a while. Before we sat at the table, you cleaned the table. You were adamant about hygiene, and so you wiped everything before use, even the plates you had just taken out of the dishwasher. The water in the water boiler had to be changed before every use because who knows for how many days it had been in there. You had used it that morning, but still, the water had to be changed. You told me to wear house slippers when I went into the bathroom.

You cooked the meat then set it next to the rice on the plates. Then, you lit the candles and placed them on the table. I took small bites, to make it last longer. It wasn’t the food that made the evening resemble perfection, it was the fact that we were there, on the balcony, and the world was watching us. I wanted the world to envy us, to wish to be there with us, or live through a similar moment.

I couldn’t go into the bedroom. I tied a rubber band around the thought.

I heard a noise coming from the bedroom. A thump on the floor. I stood and listened, but the sound did not occur again. I drained the pasta and poured the prepared sauce over it. I arranged it on a plate. Before sitting, I wiped the table clean, washed the glasses, and I, finally, sat down to eat. I did not usually say any prayers before eating, but right then I felt the compunction to do it. Not a prayer addressed to God, no, I had stopped long before that to believe there was a higher power watching over us. It was, instead, the desire to make a wish, as if the plate of pasta was a birthday cake and I had to blow the candles. I wished, most of all, to see you return, to be able to share that meal with you, to let you know that I had mastered the art of making a meal for myself. You were always accusing me of being dismissive of food when the time came to eat something. The truth was, I hated cooking because it required time I did not want or have to dedicate to it. After a hard day’s work, cooking was the last thing that went through my mind. I wanted you, not to love me, I think we were well past that, but to be happy for me, to be content that I had turned into someone you wished me to become.

The rubber band stretched. I couldn’t go into the bedroom.

After I finished eating, I went out on the balcony for a smoke. I found the ashtray with the row of half-naked women on it, which you had bought as a joke. I smiled when I saw it because it was akin to discovering a part of you. The two small chairs with the dark brown pillows on them were still there, as was the little star with the LED light inside that twinkled. When I turned it on, the star lit up and pulsed, but only a few times and then it went dead, or to faint light. A car parked in the courtyard and a man wearing sweatpants came out of it. He did not look up and went into the adjacent building.

I was afraid of going back into the apartment after I finished smoking. It looked so empty and silent from the outside. I put the dishes into the dishwasher and decided to make camp on the living room sofa. I dragged the suitcase into the room. The man on TV was still talking about immigration and the challenges it posed to the soul transfer system. New trends were developing, people asked to be transferred into bodies that lived in the developed world. The notion of citizenship was becoming superfluous. I changed channels. I locked the door and stretched out on the sofa.

Then, I fell asleep and dreamt of my grandmother, who was taking me to an abandoned house. Inside the house, there was a special room that did not have any floors. And if you opened the door and looked down, you could peer into the abyss of your mistakes. I did not see my mistakes, or sins because I woke up before I could do that. But even before I could open the door to that room, I knew what my mistakes were.

In the car, Francis did not say a word. He looked, forlornly, out the window at the passing scenery. I put my hand on his knee and asked him how he felt. It’s different now, he said and placed his hand on top of mine. Different, how? I don’t know, he replied, just different. Then he was back in his mind again. I continued talking about trivial matters. The weather had turned hectic. Sea levels had been rising alarmingly, and people were fleeing from the coasts into the mainland. Cities were disappearing. The transition between seasons had become abrupt and unforgiving as if someone up there wanted to see how we would react to that. Have you read Dante’s Inferno? Francis was looking at me now. I asked him to repeat the question. He went on. That’s how I feel, it’s like I’m in beast mode. He closed his fists, placed them together and brought them to eye level, the way children do to mime the use of a telescope. It’s like I’m looking through a plastic tube. Everything is unglued.

In the car, Francis did not say a word. He looked, forlornly, out the window at the passing scenery. I put my hand on his knee and asked him how he felt. It’s different now, he said and placed his hand on top of mine. Different, how? I don’t know, he replied, just different. Then he was back in his mind again. I continued talking about trivial matters. The weather had turned hectic. Sea levels had been rising alarmingly, and people were fleeing from the coasts into the mainland. Cities were disappearing. The transition between seasons had become abrupt and unforgiving as if someone up there wanted to see how we would react to that. Have you read Dante’s Inferno? Francis was looking at me now. I asked him to repeat the question. He went on. That’s how I feel, it’s like I’m in beast mode. He closed his fists, placed them together and brought them to eye level, the way children do to mime the use of a telescope. It’s like I’m looking through a plastic tube. Everything is unglued.

I wrote The Effete, a novel set in an utopian community on the outskirts of an unknown city, in 2013, and for the first time in my writing career I was experimenting with names. I don’t usually give names to my characters because most often I’m afraid that people who know me will be able to recognize themselves in the things I write about. By not using names, I also want to maintain the widest aperture to the reader, let him or her do part of the work of fiction, fill in the blanks, as well as liberate my characters of a certain excess of interpretation. From this point of view, The Effete is different: though there are no more than a couple of characters, they have a name, they are identifiable. The very title of the novel is a name in itself, one describing a social category. In the Theatür, the motherly company that in the end becomes a way of life and a metaphor for the reality that I myself have been experiencing for quite a while, “the effete” are those who have been expelled from the ranks of presumably “normal” human beings and who have sought refuge in a world where they are being told exactly what they are. No embellishments, no fancy language, the effete know where they stand. The rest is variation. And love.

I wrote The Effete, a novel set in an utopian community on the outskirts of an unknown city, in 2013, and for the first time in my writing career I was experimenting with names. I don’t usually give names to my characters because most often I’m afraid that people who know me will be able to recognize themselves in the things I write about. By not using names, I also want to maintain the widest aperture to the reader, let him or her do part of the work of fiction, fill in the blanks, as well as liberate my characters of a certain excess of interpretation. From this point of view, The Effete is different: though there are no more than a couple of characters, they have a name, they are identifiable. The very title of the novel is a name in itself, one describing a social category. In the Theatür, the motherly company that in the end becomes a way of life and a metaphor for the reality that I myself have been experiencing for quite a while, “the effete” are those who have been expelled from the ranks of presumably “normal” human beings and who have sought refuge in a world where they are being told exactly what they are. No embellishments, no fancy language, the effete know where they stand. The rest is variation. And love.